The Japan Patent Office (JPO) dismissed an opposition against trademark registration no. 6227071 for work mark “SMART TYRE” over a tire and other goods in class 12 claimed by Daimler AG who argued the mark is confusingly similar to senior registrations for the “SMART” mark in the same class owned by smart Automobile Co., Ltd.

[Opposition case no. 2020-900136, Gazette issued date: December 25, 2020]

“SMART TYRE”

The opposed mark, composing of wordmark “SMART TYRE” written in standard character, was sought for registration by Sumitomo Rubber Industries, Ltd., famous for “DUNLOP” tire brand, by designating various tires, automobiles, motorcycles, bicycles, and its structural parts and accessories in class 12 on August 21, 2018.

[TM Application no. 2018-105830]

The mark was registered and published for opposition on March 10, 2020.

Opposition by Daimler AG

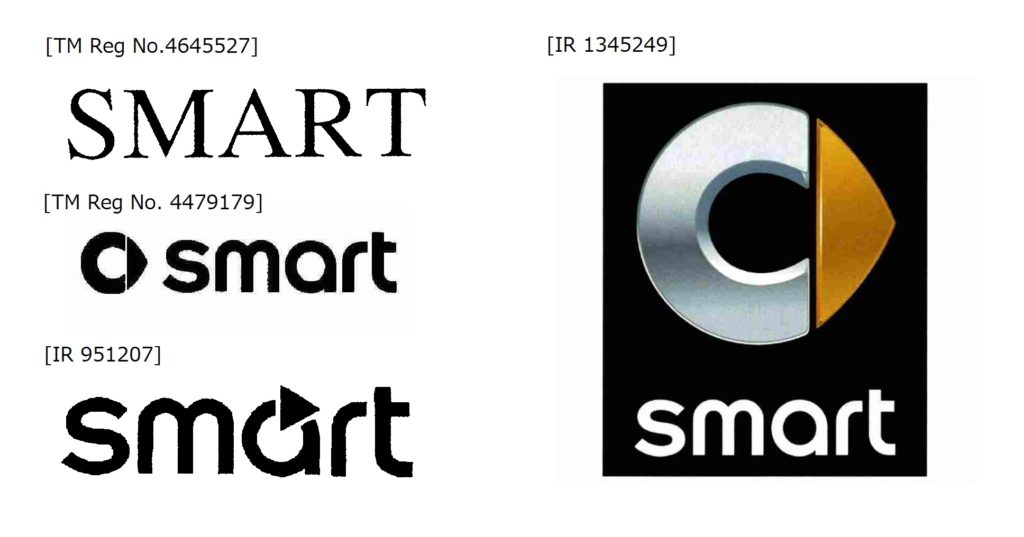

On May 11, 2020, just before the lapse of a two-months opposition period, Daimler AG filed an opposition before the JPO and claimed that the opposed mark shall be canceled in contravention of Article 4(1)(xi) and (xvi) of the Japan Trademark Law by citing senior trademark registrations for the “SMART” mark (see below) in class 12, which the opponent allegedly has used on the micro compact cars since 1998.

Daimler AG argued the opposed mark is a composite mark consisting of “SMART” and “TYRE”. The term “TYRE” undoubtedly lacks distinctiveness in relation to the goods of ‘tires’. If so, the dominant portion of the opposed mark shall be the term “SMART” which is identical to the cited marks. Besides, the ‘tires’ is considered as a structural part of automobiles and thus deemed similar to automobiles designated under the citations.

Therefore, the opposed mark shall be canceled based on Article 4(1)(xi).

Article 4(1)(xi) is a provision to prohibit registering a junior mark that is deemed identical with, or similar to, any senior registered mark.

Board decision

Surprisingly, the Opposition Board of the JPO found the opposed mark “SMART TYRE” shall be considered in its entirety irrespective of the fact that the term “TYRE” means ‘tire’. In addition, the Board held the opposed mark does not give rise to any specific meaning at all, and it is deemed a coined word.

Based on this finding, the Board assessed the similarity of marks as follows.

From appearance, both marks are sufficiently distinguishable since the opposed mark contains the term “TYRE” unlike the citations.

Phonetically, the opposed mark consists of seven sounds. In the meantime, the citations have four sounds. Due to the difference, relevant consumers are unlikely to confuse both marks.

The citations truly give rise to adjective meanings of ‘clever, bright, intelligent’. Meanwhile, the opposed mark has no meaning.

Therefore, the opposed mark “SMART TYRE” is dissimilar to the citations from visual, phonetical, and conceptual points of view even if the goods in question is deemed similar to the citations.

By stating that the term “TYRE” is inseparably and tightly incorporated into the opposed mark to the extent that relevant consumers would not conceive it as a descriptive indication in relation to the goods of class 12, the Board concluded the opposed mark shall not cause misapprehension of quality even when used on goods in question other than tires.

Based on the foregoing, the Board decided the opposed mark shall not be canceled in contravention of Article 4(1)(xi) and (xvi) of the Trademark Law and allowed “SMART TYRE” to survive.

The JPO’s finding does not look reasonable to me. It is clear that “TYRE” indicates ‘tire’. I suppose the Board rather should have mentioned the term “SMART” nowadays becomes generic when used in combination with the descriptive word(s) on the goods in question.